San Diego’s “Impossible Railroad”

by Richard V. Dodge

As printed in DISPATCHER #6, June 29, 1956

A publication of the Railway Historical Society of San Diego

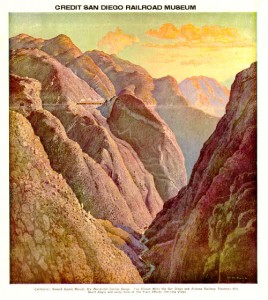

Nature never intended that a railroad should be built through magnificent Carriso Gorge. When surveys were being made for the San Diego and Arizona Railway, it was called the “impossible railroad” by several reputable engineers. But the S. D. & A. meandered the length of the Gorge by a tortuous route.

Ever since the Mexican War, the hue and cry had been for a direct rail line to the east, first from military necessity, then to develop the Port of San Diego. Even when the California Southern Railroad, now Santa Fe, was built, 1881 to 1885, no direct line was achieved and when the Santa Fe management moved the offices to Los Angeles and the shops from National City to San Bernardino, making San Diego’s bought and paid for railroad nothing but a branch line, promotions for a direct line again sprang up. None was brought into fruition. So, in 1906, there was no hope of ever financing a road, though some $40,000 had been raised for surveys and rights-of-way for a proposed route named San Diego & Eastern Railway.

Imagine the shock, the surprise and then renewed confidence of the people of San Diego when the San Diego Union of December 14, 1906 displayed the almost incredible headlines: RAILROAD FROM SAN DIEGO TO YUMA IS NOW ASSURED. Named San Diego and Arizona Railway. Line Will Be Built and Owned By Spreckels Interests.

The San Diego and Arizona Railway Company had been incorporated secretly in June by John D. Spreckels, his brother Adolph B., they being the sons of Claus, the Sugar King of San Francisco; John D., Jr.; William Clayton and Harry L. Titus.

The San Diego and Arizona Railway Company had been incorporated secretly in June by John D. Spreckels, his brother Adolph B., they being the sons of Claus, the Sugar King of San Francisco; John D., Jr.; William Clayton and Harry L. Titus.

All subscribers to the San Diego & Eastern fund were reimbursed in full. Colossal condemnation proceedings were started to obtain rights-of-way and land for stations, yards and other facilities. Surveys were begun and over 1,000 miles of lines were run.

Eventually it became known that the originator of the road was none other than Edward H. Harriman, the canny wizard of the railroad world, who was in control of the Union Pacific Railroad, the Southern Pacific Company and other lines.

Harriman had become familiar with fertile Imperial Valley when the President of the United States of America, Theodore Roosevelt, pleaded for him and the Southern Pacific to stop the rampaging Colorado River, which had broken through its bank and was flooding the below sea level areas of the recently developed Valley. By giving rock trains right over all others, the herculean task of dumping rock into the break faster than the swirling waters could carry it away was finally accomplished. Harriman had then visualized the advantages of a direct railroad to tidewater in San Diego. So he joined forces with J. D. and A. B. Spreckels to actually build the line.

The history of the San Diego and Arizona is a narrative of one calamity after another.

Ground breaking ceremonies were held on September 7, 1907, near the foot of 28th Street in San Diego. The first preliminary grading contract was let.

Calamity No. 1: The country was then plunged into a short but severe depression. Money for construction was almost impossible to obtain. Work was hindered.

The first grading was started in January 1908 and work continued on the surveys. Two All-American routes via Dulzura and one through Lower California (now generally known as Baja California), Mexico, were pronounced practical. Detailed estimates showed the costs of the All-American route to be the higher. John D. went to Mexico City and obtained the concessions required from the Mexican Government.

By 1909 conditions were improved. Robert Sherer & Sons Company was awarded the actual grading contracts from San Diego to the border and through Baja California to Tecate, including the boring of two tunnels near the location of the present Rodriguez Dam.

By 1909 conditions were improved. Robert Sherer & Sons Company was awarded the actual grading contracts from San Diego to the border and through Baja California to Tecate, including the boring of two tunnels near the location of the present Rodriguez Dam.

The first locomotive, No. 1, a six wheeled switch engine built at Pittsburgh, and some rolling stock were received. Rail laying was scheduled to commence and everything was looking up when:

Calamity No. 2 struck. E. H. Harriman passed on in September 1909. His successor in the control of the Southern Pacific did not conform with Harriman’s policies. The contract with the Spreckels Brothers was cancelled. The Southern Pacific would advance no more funds. This was a staggering blow to John D. He admitted that Harriman had been furnishing the money and he had been spending it. Now he would have to raise the needed capital single handed. This he determined to do.

Rails were laid to the Mexican border in February 1910. The road’s first passengers were carried into Mexico on a big excursion to Tijuana Hot Springs (Agua Caliente) on July 29. There a commemorative tablet was presented to John D. by a representative of the Chamber of Commerce. The bridge across the Tijuana River was completed by the end of the year.

Rails were laid to the Mexican border in February 1910. The road’s first passengers were carried into Mexico on a big excursion to Tijuana Hot Springs (Agua Caliente) on July 29. There a commemorative tablet was presented to John D. by a representative of the Chamber of Commerce. The bridge across the Tijuana River was completed by the end of the year.

Then came Calamity No. 3. A rash of revolutions broke out in 1911 in Mexico. All Mexican laborers left the job. But, in June, the insurrectionists surrendered and work could be resumed.

The second locomotive, consolidation type No. 50, built by Baldwin, had been delivered in February. Track was laid to Valle Redondo, 36 miles from San Diego, that year, elevation 766 feet.

The second locomotive, consolidation type No. 50, built by Baldwin, had been delivered in February. Track was laid to Valle Redondo, 36 miles from San Diego, that year, elevation 766 feet.

El Centro, 49 feet below sea level, was designated as the eastern terminus, instead of Yuma. The portion of the Holton Interurban Railway’s track from El Centro to Seeley would be taken over. Contracts had been let for construction to a point five miles west from Seeley and regular train service was inaugurated over the completed sections. E. J. Kallright, of the Southern Pacific, was appointed to the position of Chief Engineer.

Calamity number 4 should have been the knock-out punch, but John D’s. indomitable courage and grim determination were unconquerable. In February 1912, the Southern Pacific instituted a suit versus the J. D. & A. B. Spreckels Company to recover nearly three million dollars, the amount of funds already advanced. John D. fought this action through the courts and the suit was dismissed in 1916, compelling the Southern Pacific to retain its interests in the railroad.

The ten miles of bow knots and double horseshoe curves, gaining altitude out of Redondo through an undeveloped country, much of the construction being through solid granite, slowed progress. The feature of this section is that nearly all the ten mile stretch can be seen from Redondo. The ruling grade eastbound is 1.4%.

The ten miles of bow knots and double horseshoe curves, gaining altitude out of Redondo through an undeveloped country, much of the construction being through solid granite, slowed progress. The feature of this section is that nearly all the ten mile stretch can be seen from Redondo. The ruling grade eastbound is 1.4%.

The Spreckels interests had purchased the San Diego, Cuyamaca & Eastern Railway with its line from San Diego through La Mesa, El Cajon and Lakeside to Foster in 1909. The company was reorganized as the San Diego & Cuyamaca Railway. In March 1912, that road and the San Diego Southern Railway were consolidated into the San Diego & Southeastern Railway. The San Diego Southern Railway had been formed in 1908, merging the Coronado Railroad with the National City & Otay Railway, which latter John D. had previously purchased.

By the end of 1913, the rail front was about eight miles west of Tecate at an elevation approximately 1,500 feet. On the Eastern Division, Coyote Wells, elevation 272 feet and 26 miles west of El Centro, was reached in April 1914. Regular trains were running from El Centro to Dixieland, 19 miles. Passenger service to Tecate, 52.3 miles from San Diego, elevation 1,685 feet, was begun in September 1914.

Next came Catastrophe Number 5, with the declarations of war in Europe, starting what developed into World War One. There was no money available for railroad construction projects. But, someway, John D. kept the work going. Political relations with the Republic of Mexico became strained. Some troops were landed at Veracruz. As there was a serious risk of war, all American citizens were ordered out of Mexico. However, Mexican foremen carried on the construction work nobly until the disputes were settled.

The Santa Fe Railway was then building its present station in San Diego. Negotiations were concluded for use of the new facilities, making it a Union Station, with the San Diego & Arizona paying a pro-rata of the costs. This arrangement replaced the plans for building an individual depot at Market and India Streets.

It had been the hope that the San Diego & Arizona would be completed in time for the opening of the Panama California Exposition in Balboa Park on January 1, 1915, but there was a long way to go on that date.

In January, two consolidation locomotives were delivered, bearing numbers 101 and 102. They had been built by the American Locomotive Company in Schenectady in 1914. Passenger coaches and baggage cars were received from the Pullman Company’s shops.

Railroad building in the country was now at a standstill, except on the San Diego & Arizona. The Sherer Company was awarded the contract for the grading to Campo, including the boring of tunnels numbers 3 and 4. The latter was expected to become a tourist attraction as the international boundary line is crossed in the tunnel.

Railroad building in the country was now at a standstill, except on the San Diego & Arizona. The Sherer Company was awarded the contract for the grading to Campo, including the boring of tunnels numbers 3 and 4. The latter was expected to become a tourist attraction as the international boundary line is crossed in the tunnel.

Mother Nature dealt the next blow. It was the tremendous devastation by floods in January 1916, augmented by the failure and collapse of Lower Otay Dam on the 27th. The high fill across Otay Valley was swept away, 1,000 feet of fill in Sweetwater Valley was washed out and great damage was done to the new work along Campo Creek. Engine #50 was derailed, turned over onto its left side and sank in the sand and mud in Sweetwater Valley, engineer Wilfley and fireman Schussler having narrow escapes. Train service over temporary tracks was resumed in mid-February.

The rails reached Campo, 65.3 miles from San Diego, elevation 2,585 feet, and, on October 2, 1916, a combination rail and auto service was inaugurated. It was by train to Campo, transferring there to “roomy 12 passenger chair car autos” of the White Star Motor Company to El Centro. Trains were also operated from San Diego to Tia Juana to serve the patrons of the horse races held in Tijuana at the old track near the border.

The rails reached Campo, 65.3 miles from San Diego, elevation 2,585 feet, and, on October 2, 1916, a combination rail and auto service was inaugurated. It was by train to Campo, transferring there to “roomy 12 passenger chair car autos” of the White Star Motor Company to El Centro. Trains were also operated from San Diego to Tia Juana to serve the patrons of the horse races held in Tijuana at the old track near the border.

By December, amicable relations had been re-established with the Southern Pacific, now headed by Julius Kruttschnitt, Chairman of the Board. John D. formed a partnership and it was agreed that the road would be built jointly on a 50-50 basis. The Board of Directors of the San Diego & Arizona was re-organized to admit representatives of the Southern Pacific.

Twohy Bros. Company was awarded the contract for the construction of the roadbed from the terminal east of Campo for 20 miles, including the building of the spectacular bridge over Campo Creek at Stony Canyon. The highest point on the line is reached at Tecate Divide (Hipass) with an elevation of 3,660 feet, 82.4 miles from San Diego.

Twohy Bros. Company was awarded the contract for the construction of the roadbed from the terminal east of Campo for 20 miles, including the building of the spectacular bridge over Campo Creek at Stony Canyon. The highest point on the line is reached at Tecate Divide (Hipass) with an elevation of 3,660 feet, 82.4 miles from San Diego.

1917 brought the United States into World War One. The Government seized and took over the operation of all the major railroads, under the Railroad Administration. All railroad construction was stopped. John D. overcame this calamity by making a trip to Washington and convincing the authorities of the necessity for the completion of the San Diego & Arizona Railway as a defense measure, on account of the military installations in the San Diego area. He was granted an exemption, the only one issued. But labor shortages and the high costs of materials still hindered progress.

The Directors voted to purchase the San Diego & Southeastern Railway Company in November. Both roads were owned by the same persons and the consolidation would reduce the overhead. In this transaction two saddle tank engines, 2-4-2T type, and three ten wheelers were taken over. The tank engines, numbers 2 and 5, were sold in 1919. The 4-6-0 ‘s became SD&A numbers 21, 22 and 23. In a short time they were renumbered 10, 11 and 12 respectively.

The Directors voted to purchase the San Diego & Southeastern Railway Company in November. Both roads were owned by the same persons and the consolidation would reduce the overhead. In this transaction two saddle tank engines, 2-4-2T type, and three ten wheelers were taken over. The tank engines, numbers 2 and 5, were sold in 1919. The 4-6-0 ‘s became SD&A numbers 21, 22 and 23. In a short time they were renumbered 10, 11 and 12 respectively.

Three gasoline-electric motor cars, used on commuter runs to La Mesa and Lakeside, were also acquired. They retained their road numbers, 41, 42 and 43. This assignment was continued for several years.

The California Railroad Commission authorized the installation of crossings at grade with the Pacific Coast Steamship Company’s railroad and the Santa Fe Railway and city streets from Fifth Ave. to First Ave. and at I St. An agreement had been reached with the Santa Fe whereby the San Diego & Arizona would perform the switching operations on industry spur tracks north of its main line.

Track laying was started east from Campo and the towers and piers for the Campo Creek Bridge were completed by the end of the year.

Then the final contract, covering the last twenty miles, was signed with the Utah Construction Company. This included the almost impossible stretch through Carriso Gorge. Work was started from both ends of the canyon. There were 17 tunnels to bore in the 11 miles in the Gorge proper, ranging from about 200 feet to 2,600 feet in lengths. The bench had to be carved out of the steep slopes of the canyon, sometimes as high as 900 feet above the bottom of the ravine. Wooden trestles were decided upon on account of the extreme heat during summer months. There were 14 side hill trestles, where the inside rail is on solid earth and the outer one is supported on the trestle. How this most difficult construction could be accomplished taxes one’s imagination. Expensive by-pass roadways had to be constructed around the tunnel locations. Water for construction camps was a serious problem, as always in desert locations. 20 degree curves were required at several points. From the 2,835 feet elevation at Jacumba, the descending grade with a maximum of 2.2% brought the rail level to 2,006 feet at Carriso Gorge Station. The cost of the Gorge section exceeded the wildest estimates, resulting in an expenditure of over $4,000,000 and running the entire cost of the road up to $18,000,000.

Then the final contract, covering the last twenty miles, was signed with the Utah Construction Company. This included the almost impossible stretch through Carriso Gorge. Work was started from both ends of the canyon. There were 17 tunnels to bore in the 11 miles in the Gorge proper, ranging from about 200 feet to 2,600 feet in lengths. The bench had to be carved out of the steep slopes of the canyon, sometimes as high as 900 feet above the bottom of the ravine. Wooden trestles were decided upon on account of the extreme heat during summer months. There were 14 side hill trestles, where the inside rail is on solid earth and the outer one is supported on the trestle. How this most difficult construction could be accomplished taxes one’s imagination. Expensive by-pass roadways had to be constructed around the tunnel locations. Water for construction camps was a serious problem, as always in desert locations. 20 degree curves were required at several points. From the 2,835 feet elevation at Jacumba, the descending grade with a maximum of 2.2% brought the rail level to 2,006 feet at Carriso Gorge Station. The cost of the Gorge section exceeded the wildest estimates, resulting in an expenditure of over $4,000,000 and running the entire cost of the road up to $18,000,000.

In 1918, the building of 13 miles of track to serve the Army and the Navy aviation fields located on North Island was authorized by the War Department. These tracks connected with the Coronado Belt Line from the ferry landing.

On April 16th, the officials made an inspection tour from San Diego and witnessed the closing of the final span of the Campo Creek Bridge. The rails were laid to Jacumba Hot Springs, 92 miles from San Diego, by July 18th and, on the eastern division, to the foot of the Gorge.

On April 16th, the officials made an inspection tour from San Diego and witnessed the closing of the final span of the Campo Creek Bridge. The rails were laid to Jacumba Hot Springs, 92 miles from San Diego, by July 18th and, on the eastern division, to the foot of the Gorge.

Further afflictions plagued the road in 1919. There was a world wide influenza epidemic. The construction workers in the camps in the Gorge were hard hit.

By mid-August, all except four tunnels had been completed. The next constant source of trouble was Tunnel number 8 in the Gorge, defying the efforts of the drillers to make much progress. Most of the barrel had to be cut through solid rook. When an advance was made, loosened rocks would slide down, blocking the bore. In one cave-in a workman was buried and fatally injured. The completion of this 2,500 foot tunnel delayed the opening of the line. For a time it was believed that a shoo-fly would have to be built around it. Track laying and ballasting were completed to the portals of the adamant tunnel and it was finally conquered, holed through and the rails were laid.

On Saturday, November 15th, the “Gold Spike Limited” made its run from San Diego to Carriso Gorge Station, carrying all the top brass and big shots of the Southwest Corner, Including Baja California. A more fitting spot for the crowning event could not have been selected.

John D. climbed onto a flat car and told briefly and modestly how he had accomplished the gigantic task. When the Southern Pacific reneged, he said, “Well, then let me do it, and from that moment on I did it and continued the building with such funds as I could spare from my business and such funds as my brother aided me with…” until the partnership with the Southern Pacific was formed.

Then he jumped down, stripped off his coat and drove the final spike. It was a real gold one, costing $286, and it was inscribed “Spike driven, by John D. Spreckels, President.” “Last spike driven, San Diego & Arizona Railway, in Carriso Gorge – November 15, 1919.”

Then he jumped down, stripped off his coat and drove the final spike. It was a real gold one, costing $286, and it was inscribed “Spike driven, by John D. Spreckels, President.” “Last spike driven, San Diego & Arizona Railway, in Carriso Gorge – November 15, 1919.”

And John D. had accomplished the so-called “impossible.” Mayor Wilde, in his comments, said: “You have often heard the remark that San Diego is a one-man town. Personally I feel proud to live in San Diego when it is referred to as a one-man town…..This afternoon you can’t give our great leader enough glory.”

The first through trains from El Centro 146.4 miles to San Diego arrived at Union Station on the afternoon of December first, powered by Southern Pacific locomotives. Parades and banquets followed. John D. said “This is the happiest day of my life.” The first freight train left San Diego that night with 20 cars.

The first through trains from El Centro 146.4 miles to San Diego arrived at Union Station on the afternoon of December first, powered by Southern Pacific locomotives. Parades and banquets followed. John D. said “This is the happiest day of my life.” The first freight train left San Diego that night with 20 cars.

Through Pullman service to Chicago was inaugurated on the 10th. The trains, displaying numbers 4 and 3, operated to and from Yuma over the Inter-California Railway but the crews were changed at Calexico. The through cars were switched to the Southern Pacific’s Golden State at Yuma.

Second trains were added in January 1920 as the “Imperial Valley Local,” numbers 6 and 7. They operated to and from Calexico. These were replaced by “mixed” trains numbers 51 and 52 in April. In November, these carried a Pullman, making connections with the Sunset Limited, #101 and 102.

A Baldwin ten wheeled locomotive, built in 1906 and formerly operated on the Bullfrog and Goldfield Railway, was purchased in 1919. It was fitted with a new boiler by the Southern Pacific and was assigned number 20. In 1920 four more ten wheelers were purchased second hand, all having been built by Baldwin in 1907. These had been Las Vegas & Tonopah Railway’s numbers 7, 9, 10, and 11 and were renumbered 24, 25, 26 and 27.

In 1921, four consolidation type locomotives were obtained from the Southern Pacific; numbers 2523, Baldwin 1907; 2720, Baldwin 1904; 2843 and 2844, built by Southern Pacific at Los Angeles in 1917 and 1918, These were renumbered 103, 104, 105 and 106. Also Southern Pacific 0-6-0 type switch engine #1046 was acquired and was assigned second #2.

The Mexican Division was changed to a separate corporate entity with the name Tijuana & Tecate Railway.

But Mother Nature still protested against a railroad through the Gorge. An avalanche of rock and earth slid down over the west end of Tunnel #7 on May 10, 1920. Inspections revealed more incipient slide formations and it was necessary to break down practically the entire side of the mountain. Trains were tied up for many weeks. The estimated cost was over a quarter of a million dollars.

In 1922, a new emblem, depicting a scene in the Gorge and lettered “San Diego Short Line”, was adopted.

In 1922, a new emblem, depicting a scene in the Gorge and lettered “San Diego Short Line”, was adopted.

Trains numbers 101 and 102 were added in November, operating through sleepers via Niland on the Sunset Limited to New Orleans, These were dropped in November 1926.

Private Car #050 had been assigned for the use of President Spreckels and had been named “Carriso Gorge.” This car was used by A. T. Mercier, new President and General Manager, accompanied by A. D. Hagaman, General Freight and Passenger Agent, for a trip to New Orleans and the east in 1923. Motion pictures of San Diego, Coronado and the Gorge were shown in the car “to sell the San Diego & Arizona to railroad men.” “Border Line Excursions” were operated in that year, fare $4.68 for the round trip.

Engine #104 and private car “Carriso Gorge” were featured in a moving picture location in the Gorge in 1923. Elmer Hall, engineer, ran #104 on this assignment, which, at times, became a little too realistic.

Engine #104 and private car “Carriso Gorge” were featured in a moving picture location in the Gorge in 1923. Elmer Hall, engineer, ran #104 on this assignment, which, at times, became a little too realistic.

With increased competition by automobile and buses, passenger service to La Mesa and Lakeside was curtailed and the gasoline motors began making five scheduled runs to Tia Juana, using Union Station for three of them.

Engine number 11 was scrapped in 1925.

Then came the sad news in 1926. John D. Spreckels passed on, on June 7th. All San Diego mourned the loss of this “big, simple, great man.”

Flash floods in December caused serious washouts west of Coyote Wells and on the Southern Pacific between El Centro and Niland. Normal service was restored in 30 days. More storm damage took place between San Diego and Garcia in February 1927.

Motor service to La Mesa and Lakeside was discontinued in 1928. However, the development of Tijuana Hot Springs into the elaborate resort of Agua Caliente, the “Deauville of the Americas,” including a new race track, resulted in the operation of two to six schedules to Agua Caliente with steam trains in addition from 1928 to the end of Prohibition in the United States.

A series of disasters struck the road in 1932.

First, a fire, possibly of incendiary origin, broke out in Tunnel 3 in Baja California in January. The portals were barricaded and sealed and the fire burned for four days. The roof caved in. The railroad was tied up for 45 days, causing a reported loss of $157,000.

Scarcely had service been resumed when a huge mountain slide, loosened by heavy rains, blocked the line in the vicinity of Tunnel #15 on March 27th. After an engineering study had been made and plans prepared for a change in alignment, about one-half mile of new roadbed was constructed, including the building of a high wooden bridge on a 15 degree curve and tunnel changes. Freight and passenger services were re-established on July 6th and 7th and the cost ran up to $317,000.

Scarcely had service been resumed when a huge mountain slide, loosened by heavy rains, blocked the line in the vicinity of Tunnel #15 on March 27th. After an engineering study had been made and plans prepared for a change in alignment, about one-half mile of new roadbed was constructed, including the building of a high wooden bridge on a 15 degree curve and tunnel changes. Freight and passenger services were re-established on July 6th and 7th and the cost ran up to $317,000.

Finally, on October 22nd. Tunnel #7 burned and it was decided to abandon it. A by-pass was built around the cliff requiring seven 20 degree curves in 1,150 feet. Trains began running on January 23, 1933.

By this time the heirs to the J. D. and A. B. Spreckels’ estate had had enough and sold their interests to the Southern Pacific. As a result, the San Diego & Arizona Eastern Railway Company was incorporated effective February 1, 1933, as a wholly owned, separately operated subsidiary of the Southern Pacific. The motive power was relettered but the old numbers were retained.

Operation of the three gasoline motors was discontinued in 1934. #41 and 43 were scrapped and #42 was dismantled in 1939. The body of the latter was used a field office in 1940.

Operation of the three gasoline motors was discontinued in 1934. #41 and 43 were scrapped and #42 was dismantled in 1939. The body of the latter was used a field office in 1940.

Another 0-6-0 switch engine was added to the roster in 1936, being Southern Pacific number 1096, built by Baldwin in 1902. It was assigned SD&AE number 3.

Steam engine number 10 was scrapped in 1938.

Floods hit again in 1939. The branch line along the San Diego River between Santee and Lakeside was badly washed, resulting in abandonment. In a few years the portion of this branch between El Cajon and Santee was also abandoned and the track was torn up.

1940 saw the retirement of steam locomotives numbers second 2, 24 and 25, all being scrapped. Number 3 was returned to the Southern Pacific and became Harbor Belt #3, then Pacific Electric #1508. It was scrapped in 1947.

Engine numbers 20, 26, 103, 104 and 106 were taken over by the Southern Pacific in the first half of 1941. They were re-lettered Southern Pacific Lines and were renumbered 2385, 2386, 2523, 2720 and 2844 respectively.

Then came Pearl Harbor, December 7, 1941, and the United States was plunged into World War Two. The war emergency created an immense increase in traffic, in both the freight and the passenger departments. Many engines were obtained from the Southern Pacific, three from the Northwestern Pacific and some from other roads. Engine number 2385 was returned to the SD&AE on lease in 1943.

The passenger train connection was changed from the Golden State to the Californian, using train numbers 362 and 363 on the SD&AE.

With the surrender of the Japanese in 1945, traffic quickly dropped to normal.

New direct passenger service to Chicago was widely advertised in 1947 in connection with the Southern Pacific’s Imperial which operated via El Centro and the Inter-California Railway through Yuma. Leaving San Diego at 10:15 a.m. you could “thrill to a daytime trip through the spectacular Carriso Gorge.” The consist included a “dollar saving” Tourist Sleeper, in addition to the Standard Pullman and the chair car. Two months later the leaving time was changed to 2 p.m. Soon the connection and ‘switching operations were performed at Calexico instead of Yuma.

Engine number 12, which had since seen service as Mexicali Y Golfo 12 and Southern Pacific 12, was scrapped in 1947.

Passenger service was discontinued on mixed trains numbers 451 and 452 in 1948, except on the Tijuana & Tecate division.

Ownership of locomotives numbers 2385, 2386, 2523, 2720 and 2844 were again placed in the San Diego & Arizona Eastern in September 1948. They were re-lettered and renumbered 20, 26, 103, 104 and 106. All except number 20 were operated on divisions of the Southern Pacific, instead of on the SD&AE.

In 1940 the leaving time of passenger train number 362 was changed back to 10:15 a.m.. In 1950 the departure time was advanced to 7:05 a.m. and the tourist car was discontinued.

The first Diesel-Electric locomotive, Southern Pacific number 5217, to pull a freight train over the mountains left El Centro on February 5, 1950, on a trial run. Officials on board were S. A. Lamey, Trainmaster, Yardmaster and Chief Operating Official, Carl Eichenlaub, Division Engineer (now superintendent) and E. Harrison, Dispatcher at Mexicali. If diesels prove satisfactory, Harrison said, they will also be used to pull passenger trains. Later one was tried out on the El Cajon branch and other assignments.

After passenger traffic had been discouraged almost to the vanishing point, the San Diego & Arizona Eastern Railway filed application with the California Public Utilities Commission on July 17th for authority to abandon its passenger service. Many protests were raised but to no avail. The Public Utilities Commission granted permission for the abandonment on December 19th. The last direct passenger train service to the east, for which the old timers had fought so tenaciously down through the years, left San Diego at 7:05 a.m. on January 11, 1951, with engine Southern Pacific number 2373 on the point. The final westbound train was pulled by engine number 2383, marking the end of an era. With it came the announcement that freight service will be converted to diesel power.

After passenger traffic had been discouraged almost to the vanishing point, the San Diego & Arizona Eastern Railway filed application with the California Public Utilities Commission on July 17th for authority to abandon its passenger service. Many protests were raised but to no avail. The Public Utilities Commission granted permission for the abandonment on December 19th. The last direct passenger train service to the east, for which the old timers had fought so tenaciously down through the years, left San Diego at 7:05 a.m. on January 11, 1951, with engine Southern Pacific number 2373 on the point. The final westbound train was pulled by engine number 2383, marking the end of an era. With it came the announcement that freight service will be converted to diesel power.

Engines numbers 20, 27 and 50 were scrapped in 1950 and number one, “La Una,” and 26 in 1951. Numbers 101 and 102 followed in 1953.

Engine number 104 was retired in 1954 and the Southern Pacific offered to donate it to the City of San Diego or other responsible authority for exhibition purposes. The Railway Historical Society of San Diego took up the task of preserving this Baldwin consolidation. After the City had declined to accept the gift, the Society made the arrangements for placing the locomotive on permanent display in the San Diego County Fair Grounds at Del Mar, along with the “Carriso Gorge,” President Spreckels’ private car which was also donated by the Southern Pacific. The locomotive and the car were delivered in October 1955.

At the end of 1955, locomotives numbers 103, 105 and 106 were still on the active list of the Southern Pacific, but they will undoubtedly be scrapped when their time runs out and they need major repairs.

Now San Diego’s “Impossible” Railroad is an 100% dieselized freight only line except for the “Mixto” through Baja California and the “Operating Ratio” has improved remarkably. At this time, a hog can thrill to the awe-inspiring vistas from his car in the train moving cautiously through Carriso Gorge but you, the traveling public, can not.

If ever a railroad was a monument to one man’s undaunted courage, indefatigable energy and steadfast determination to surmount overwhelming odds, the San Diego & Arizona Eastern Railway is a vibrant memorial to John Diedrich Spreckels, the last of America’s great railroad builders.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS; Serra Museum, The San Diego Union, Railroad Boosters’ brochure. Railway & Locomotive Historical Society Bulletin #71, John H. Andert, S. A. Lamey and other SD&AE employees.